THE HISTORY OF EASTCOTE

The Origins

The first documentary reference to Eastcote was in the mid-thirteenth century, but it existed before that as a settlement near the River Pinn in a cleared area of woodland. It was part of the Manor of Ruislip, which was referred to in the Domesday Book of 1086. By the middle of the thirteenth century Ruislip was divided into three tithings: Westcote (the western settlement, now Ruislip), Ascot or Eastcott (the eastern settlement, now Eastcote) and Norwood (the settlement to the north of the woods, now Northwood).The divisions of Westcote and Ascott/Eastcott survived until 1833 before being discontinued as “useless and unnecessary”.

Farming and settlement

From medieval times until the twentieth century, the majority of the population in Eastcote was engaged in farming and related trades. Agricultural methods changed little from medieval times until the 1804 Enclosure Act. This resulted in large hedged fields being created predominately to the south where Eastcote bordered on to the parishes of Northolt and Greenford. Previously this area had been farmed as open arable fields divided into strips for cultivation by individual villagers. After enclosure, tracks leading to these strips from the village became a road, now the modern Field End Road.

A feature of Eastcote village was the many “ends”, mostly with small greens, which denoted the boundaries of scattered hamlets. Field End, at the junction of Field End Road with Bridle Road, stood at the end of the open fields, while Hale End, at the bend in the road near Highgrove, marked the western edge of the village. The eastern limit was Pope’s End at the junction of the High Road, Cheney Street and Cuckoo Hill.

Elizabethan buildings

By Elizabethan times the centre of Eastcote had become consolidated along the High Road and Field End, with a few scattered buildings along the ancient ways of Fore Street, Gowle (Joel) Street, Popes End Lane, Chaynye (Cheney) Street and Wylcher (Wiltshire) Street which led to the common pastures in the north. A document called the 1565 Terrier, drawn up by King’s College, Cambridge, the Lords of the Manor of Ruislip, to record their property, gives a good indication of the pattern of settlement in Eastcote. For example, listed in the High Road are Ramin, the Old Shooting Box, Flag Cottage, the Old Barn House and Eastcote Cottage, while in Fore Street there is Four Elms Farm. In Wiltshire Lane there is Ivy Farm and in Cheney Street is Horn End. It is very fortunate that a total of 19 buildings mentioned in this 1565 Terrier are still in existence in Eastcote, although some have been substantially altered.

|

|

[credit: R. Gray] |

Nineteenth century

Throughout the centuries agriculture was the mainstay of Eastcote. But it was the nineteenth century which saw the heyday of the gentry landowners, with their large estates, who provided employment for most of the villagers. Eastcote was the favoured location for the gentry rather than Ruislip or Northwood, with eight of their houses being found here. However in the 1850s and 1860s there was some more modest housing. Four pairs of villas known as Field End Villas were built which attracted the first group of professional people, such as bankers, doctors and civil servants to the area. They could combine having access to London with the rural delights of Eastcote, bearing in mind that the nearest stations at that time were Hatch End and from 1887 Pinner.

At the end of the century some larger architect designed houses were built for specific clients who welcomed the quiet and seclusion of the area. Two examples, both still standing, are Eastcote Point, Cuckoo Hill built in 1896 and Eastcote Place (now in Azalea Walk) built in 1897. The latter was requisitioned for various operations during the Second World War.

But despite the presence of this small group of professional middle class people, the overall feel of Eastcote was of an isolated, agricultural village with few facilities. There was no parish church; parishioners had to go to St Martin’s in Ruislip. However the seeds of Methodism had been sown by Adam Clarke, a Methodist scholar and preacher while he lived at Haydon Hall in the 1820s. As a result, in 1847, the Methodist Chapel was opened in Chapel Hill at the bottom of Field End Road and this provided the only place of worship until later developments in the twentieth century. The nearest schools were in Ruislip and Northwood apart from the small private institution of “Miss Carter’s Young Ladies School” at Flag Cottage, High Road which operated from 1887-1913.

The Great Houses

No history of Eastcote is complete without mentioning the three largest houses known as “the Great Houses” which were at the pinnacle of their importance in the nineteenth century. The first was Eastcote House, which started life as a timber-framed house called Hopkyttes. This was in the continuous ownership of the most prominent local family, the Hawtreys (later the Hawtrey Deanes), for over 400 years. This stability meant they were regarded as the most influential local family and they were viewed as the de facto lords of the manor. After the Enclosure Act they became the largest landowners in the parish after King’s College, Cambridge.

[credit: Hillingdon Local Studies] |

|

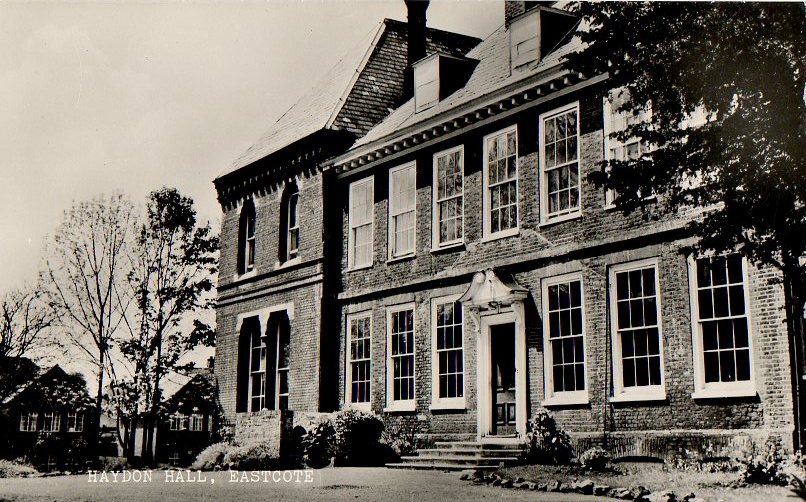

On the opposite side of the road to Eastcote House was Haydon Hall. This was built in 1630 by Lady Alice, Dowager Countess of Derby, but was completely rebuilt in 1720 in the classic style by new owner Thomas Franklin. In the nineteenth century Lawrence James Baker added two wings to the house and developed Haydon Hall as a shooting estate, building many attractive estate workers’ cottages such as New Cottages opposite Pretty Corner and Wood Cottages, Fore Street which still survive.

Twentieth century – the early years

The extension, from Harrow to Uxbridge, of the Metropolitan Railway, which passed through Eastcote fields south of the village, was to change everything. Eastcote Halt opened in 1906 and Eastcote suddenly became accessible to many more people. The centre of Eastcote shifted south, away from the old village.

Developers saw the potential of Eastcote. “Arts and crafts” style houses appeared in Catlins Lane, Cheney Street and Bridle Road. Field End House farmland was sold to the British Freehold Investments Syndicate who laid out a network of roads, recognisable by the use of trees names for their roads. Individual plots were sold for building; the first houses appearing in Elm Avenue, Lime Grove, Myrtle and Acacia Avenues.

1920s and 1930s

Ralph Hawtrey Deane (of Eastcote House) sold off his lands along Field End Road. In the mid-1920s Tellings developed Morford Way and Morford Close and built Eastcote’s first row of shops, Field End Parade, along with a community hall which became the Ideal Cinema. Rotherhams Estates and T. F. Nash both built “Deane Estates”, Rotherhams on the west side of Field End Road, Nash on the east, along with the shops of Devon Parade and Deane Parade to serve the incomers needs. South of Eastcote Halt, building continued in Woodlands Avenue. Davis Estates built on the site of the Pavilion and developed the “Tudor” named streets across the road. Further north, the Eastcote Park Estate was built by Comben and Wakeling on Eastcote House grounds. Fore Street Farm was demolished to make way for a mixed development.

Rise in population

From just 600 people at the beginning of the century, by 1939 the population of Eastcote had increased to 15,000. This led to the establishment of a separate parish of Eastcote. The new church of St Lawrence opened in 1933. St Thomas More Catholic Church opened in 1937, and St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church (now United Reform) in 1939. Eastcote Halt could no longer cope with the increased number of travellers, so a new Eastcote station was built to the modernist designs of Charles Holden. It would have been officially opened in 1939 had the Second World War not intervened.

Eastcote’s secret

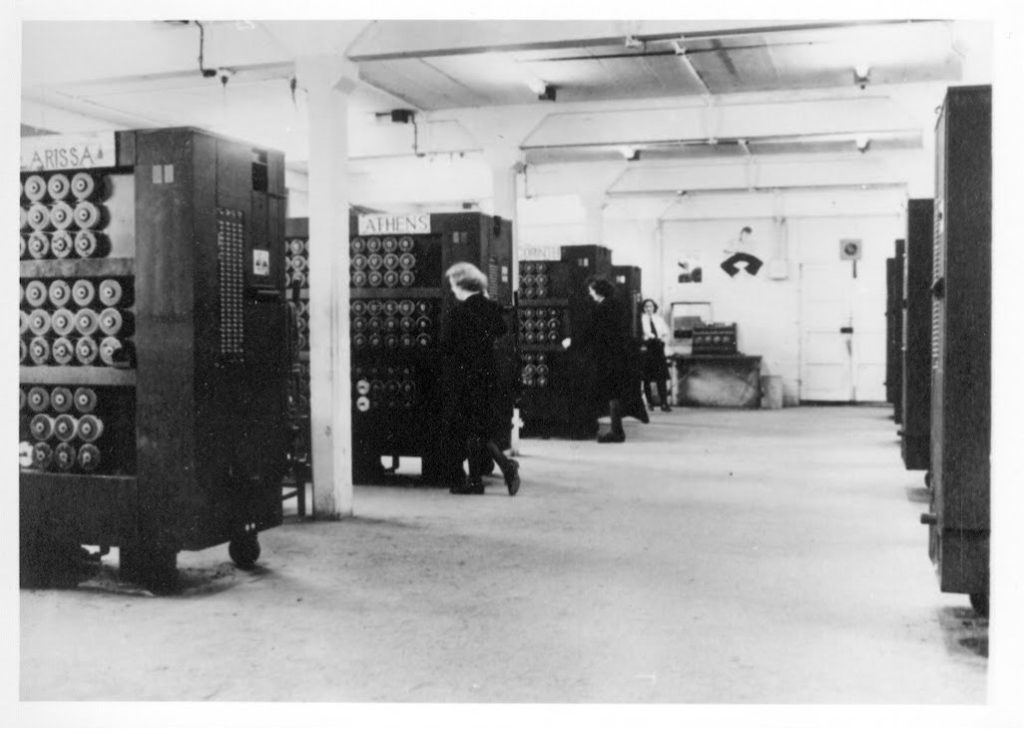

The significant part that Eastcote played in the Second World War was not known till many years later. The MOD site, between Eastcote Road and Lime Grove, was known during the war as HMS Pembroke. It served as an important outstation to the now renowned Bletchley Park. 800 Wrens, supported by 100 RAF technicians, operated 110 bombes, the machines which were used to identify and break German codes. Further information about this is included below.

1950s and 60s

After the war, GCHQ operated from here, until it relocated to Cheltenham in 1954. The site, now known as Pembroke Park, is currently being developed for housing. Some of the people and places have been commemorated in the names of the roads and buildings.

Several old farms and cottages were demolished after the war. The Wesleyan Chapel in Field End Road was finally replaced by Eastcote Methodist Church, on the other side of the road, in 1951. The chapel was demolished in 1962. Of the three great houses, by now all in the ownership of the local authority, only Highgrove House has survived. Eastcote House was demolished in 1964, followed by Haydon Hall in 1967. However several new schools were built: Field End Junior (1947) and Infants (1951), Coteford Junior (1952), Newnham Junior and Infants (1952), St Nicholas Grammar (1955) and St Mary’s Grammar (1957), now combined as Haydon School, and a new public library (1959). The Community Centre in Southbourne Gardens opened in the 1950s.

|

|

|

Eastcote is still evolving. There is regret at the loss of some of the historic buildings, yet many have survived. These, as well as many open spaces, including remnants of the parklands of old estates, serve as a reminder of times past.

Compiled by the Ruislip, Northwood and Eastcote Local History Society. ©RNELHS 2010

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pre War

|

A descendant of an ancient Eastcote family reveals The Uxbridge Gazette via www.lawrence-rand travelled across the globe for a reunion at the site of her ancestral home. Jenny Armour flew from Australia, and on Thursday last week made her first visit to Eastcote House Gardens, the grounds former home of her ancestors The Hawtrey family. Mrs Armour emigrated to Australia more than 30 years ago, but once worked as a librarian at Ruislip Library. Despite living in Ickenham and then Ruislip from an early age, she did not learn of her family connection to the house until after she had moved Down Under. On a trip to England, she went to a conference about tracing your past. Organised by the BBC’s Who Do You Think You Are? programme, she learned she belonged to the Hawtrey family.  The Hawtrey family lived in Eastcote House from 1525 when Ralph Hawtrey married Winifred Walleston and inherited her family cottage. Ralph built on the cottage and it became Eastcote House. It was lived in by the Hawtrey family and then their descendants the Deanes, for 400 years. Ralph Hawtrey was the 4th son of Thomas Hawtrey who then owned Chequers, which is now the country retreat of the Prime Minister. Mary Hawtrey, a grandaughter of Ralph and Winifred, married Sir John Bankes of Corfe Castle and Kingston Lacy and became Lady Bankes, heroine of the English Civil War when she defended Corfe Castle against Cromwell’s army for three years see landedfamilies-bankes-of-kingston-lacy. Seven of Lady Bankes’ 14 children were born in Eastcote and baptized at St Martin’s Church in Eastcote Road, Ruislip, where she is buried. The family shields are formally described in heraldic terms as follows; On a lozenge: Sable, a cross engrailed argent (should be ermine) between four fleur de lys Or (BANKES). Impaling Argent, three lions passant guardant in bend sable crowned or double cotised sable (HAWTREY). Argent a bend wavy gules charged with three plates in dexter chief a rose gules (WARRENDER). St Martin’s churchyard writes Mary Pache in rnelhs journals 2010 , is the memorial stone of Alice and Eleanor Warrender. They were of a family of six siblings with aristocratic roots in Midlothian. Their father was Sir George Warrender, 6th Baronet of Lochend and Bruntsfield, and they inherited Highgrove in 1894. Eleanor is remembered as the lady who lived at the big house. Fig. Shields of Prominent Families of Eastcote have the shields of each family; Bankes and and Hawtrey shields attrib – middlesex-heraldry.org.uk . Warrender shield attrib – wikimedia.org Blazon_of_Warrender_Baronets_of_Lochend. and wiki Line_engraving_of_Alice_Spencer (Works in public domain where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years). |

Fig. Shield of Eastcote Hypothetical/Supposition. A pentagonal shield with upper, centre and lower parts. The upper part could contain elements of the arms of a prominent families connected to Eastcote and a symbol from a prominent bygone Eastcote manor house. The centre part could contain the representations of Eastcote as an urban place. A number of candidates could be the Eastcote House stables, elements of the Middx shield, the RNUDC Shield, local architectural references, park or green spaces, bridges, railways, local churches, village references, geographic features or anything collectively the people wish for.

The symbols here are from the time just before south Eastcote was developed, the contribution towards the war effort and a nature element. A rollercoaster symbol (Icon made by Pixel perfect from www.flaticon.com) License; Free for personal and commercial purpose with attribution) denotes the main attraction for Londoners for rest and recreation as Eastcote’s Fairgrounds south of the railway line lay in open lands meaning many thousands of visitors in its heyday. The wartime effort is signified by the beacon (the symbol here sourced from The Book of Traceable Heraldic Art (editor; M. Cavalletto) free use within the Society for Creative Anachronism (SCA)), an early warning system against the approach of the enemy. It is depicted as a fire basket on a pole with a ladder leant against it. The River Pinn provides the nature element depicted by the bridge and blue channel. The nearest fairground reference in heraldic vocabulary is a pavilion tent with flag. However, this rollercoaster symbolises not only the fairground but also a vehicle and wheeled movement on rails of the modern day train. Lower right of centre part is a the Vine&Grape motif from the mezzanine banister posts of Eastcote House Garden stable. Upper right of centre part is a motif of the Tudor style decoration of Haydon House Lodge. The upper part or Chief takes Lion Passant Guardant, Ermine and a Fret. The lower part or base of shield could contain bend wavy with plates an element from the representation of another prominent family of Eastcote.

Try this at home. Perhaps, some designs could be posted here. |

<<Figure journeys to Warrender Park just West of the Eastcote Main Parade. archive.hillingdon.gov.uk explains that the Park was part of the larger Highgrove Estate and was inherited by the Warrender family in 1894. Miss Eleanor Warrender sold just over 10 acres of the estate lying to the south to the Ruislip-Northwood Urban District Council in 1935 for use as a recreation area with a children’s playground, sand pit and tennis courts. There is the fine pair of ornamental wrought iron gates at the Lime Grove entrance. Made in the 1870s for the galleries of a famous London art dealer and in 1935 when they were replaced, the Eastcote Association managed to acquire them and arranged for them to be erected at Warrender Park.

Figure>> journeys to Eastcote House Gardens from Warrender Park. parksandgardens.org explains that ‘…..within the grounds are the old Coach house, 17th-century walled garden, 18th-century dovecote and a ha-ha. There are many fine mature trees and more recent garden features include a herb garden planted for Queen Elizabeth’s Silver Jubilee in 1977, orchard, rockery and wildflower meadow. History This is the gardens and small part of the former grounds of Eastcote House, the home of the Hawtrey family from 1532. Built on the site of an older house, Eastcote House stood close to the junction of Eastcote High Road and Field End. The grounds were purchased by Ruislip-Norwood UDC in 1938 as public open space. The house was initially used for communal activities but demolished as unsafe in 1964…..’ wikipedia EHG states that ‘…..Hillingdon Council provided a £150,000 grant in September 2010 for the restoration of the buildings. In April 2011, the council joined with the Friends to seek funding of up to £1 million from the Heritage Lottery Fund for restoration work. The coach house was converted to a tea room. The gardens received the Green Flag Award in 2011….’

First World War

The significant part that Eastcote played in the First World War is embodied in the Eastcote Cross War Memorial. Fig 1 shows how the site was before the current layout that we see today. Fig 2 shows the original placement of the memorial.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Second World War

|

|

|

| Fig 3 Wrens in the Bombe Bays at Eastcote outstation | Fig 4 Bombe Operator Interview |

|

|

|

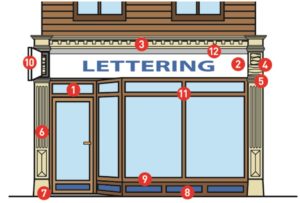

Shaping the Main Parade Today; Shopfronts National and Borough Wide Planning Guidance

| The National_Model_Design_Code.pdf from the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government provide detailed guidance on the production of design codes, guides and policies to promote successful design. | Page 22 section 53 says;…. The identity of an area comes not just from its built form and public spaces but from the design of its buildings. This is not about architectural style, but about key principles of building design. All new buildings should relate to the architectural character and materials of the surrounding area……. |

|

|

|

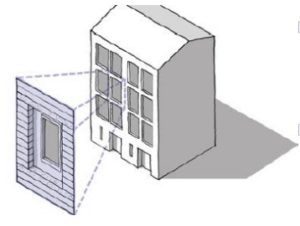

| The National_Model_Design_Code.pdf section 53 part vii proposes guidance on Detailing: ……….The use of colour, quality of materials and detailing, drawn from the surrounding context, e.g. an area might be characterised by the use of a particular type of brick. A degree of complexity will ensure that buildings are attractive from a distance and close-up……. The figure below shows how depth and interest can be created with window details. | Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) are prepared by Borough Councils as part of its planning policy framework. |

|

|

|

| West Suffolk Shopfront and Advertisement Design Guidance Feb 2015 says;……. Good design and high qualityenvironment go hand in and. A carefully designed and eye-catching shopfront is good for business and can make a positive contribution to the character of the street and the vitality of our retail areas…….. | Hillingdon’s Supplementary Supplementary Design for shopfronts is incorporated Hillingdon’s Local Plan Part 2 – Development Management Policies and says; …..Good design and high qualityenvironment go hand in and. A carefully designed and eye-catching shopfront is good for business and can make a positive contribution to the character of the street and the vitality of our retail areas…. |

|

|

|

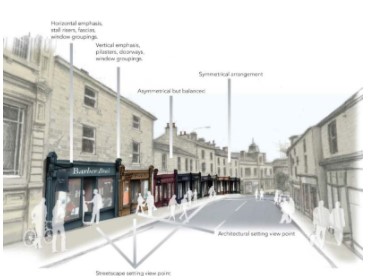

<< Figure © 2021 Google. Eastcote is a pre war main parade but modern shopping parades adopt the practices outlined above. Here is a new development in Colindale North London. Fascias are aligned horizontally and have separation from the residential upper storeys. Signage is simple but effective, balanced between commercial premises and placed within shop frontage (the shop glazing extent). There is natural separation between shopfronts and whilst there are no pilasters, the brickwork from the upper storeys is retained (at ground level). Shopfront mullions are in consistent pitch along the parade. Clutter is minimised with no hanging signs, awnings, wires, hooks, alarm boxes etc. the commercial premises have the required signage.

Figure>> © 2021 Google. Just around the corner of the main parade above is a sun drenched smaller shopping parade. Modest in scale nonetheless the clean lines are pleasing. Internal air conditioning and solar reflecting tinted glazing obviate soft fabric, cumbersome awnings. Whilst modern designs bypass classical features and motifs nevertheless repetition, proportion, vertical emphasis, coherent colour rendition and ground floor to upper floor consistency combine to provide an active street scene.

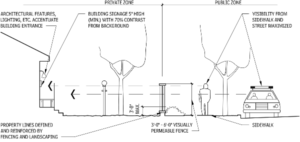

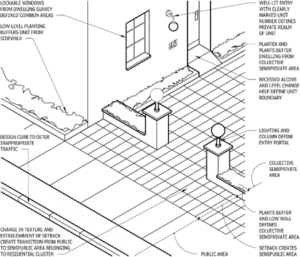

Defensible Space Theory Part 1

In his book available online at defensiblespace , concern over high crime rates and deteriorating inner-city neighbourhoods has reawakened interest in Defensible Space, architect Oscar Newman’s groundbreaking physical design approach to crime prevention. Creating Defensible Space, written by Newman published by HUD’s Office of Policy Development and Research, looks at “Defensible Space” projects since the early 1970s. This publication provides an expert review of the “Defensible Space”

Defensible Space Theory Part 2

In his book available online at Defensible Space, Oscar Newman goes onto explain the effect of building type on residents’ control of streets. Examining different building types from the viewpoint of residents’ ability to exert control over surrounding streets.

Fig 1 shows a 3-story garden apartments built at a density of 36 units to the acre. The rear courts within the interior of each cluster have been as-signed both to individual families and to families living on the ground floor have been given their own patios within the interior courts with access to them from the interior of their unit. These patios are therefore private. The remainder of the interior court belongs to all the families sharing a cluster and is only accessible from the semiprivate interior circulation space of each building, making the remainder of the interior cluster semiprivate.

Fig 1 3-story garden apartments

Fig 1 3-story garden apartments

Figure 2 shows a highrise superblock at a density of 50 dwelling units to the acre. The grounds around the buildings are accessible to everyone and are not assigned to particular buildings. The residents, as a result, feel little association with or responsibility for the grounds and even less association with the surrounding public streets. Not only are the streets distant from the units but no building entries face them. The grounds of the development are also public. All the streets and grounds are public. All the grounds of the project must be maintained by management and patrolled by a hired security force. The city streets and sidewalks, in turn, must be maintained by the city sanitation department and patrolled by city police.

Fig 2 High-rRse Superblock

Fig 2 High-rRse Superblock

Fig 3 shows a comparison of developments 2 radically different building configuration: in this case a density of 40 units to the acre with 1-to-1 parking. This is a very high density that will satisfy the economic demands of high land costs. The ‘walkup’ development achieves the same density as the highrise by covering more of the grounds (37% ground coverage versus 24%). Municipalities that wish to reap the benefits of ‘walkup’ versus highrise buildings must learn to be flexible with their floor-area-ratio requirements to assure that they are not depriving residents of a better housing option in order to get more open ground space that has little purpose.

Fig 3 Comparison of Developments

Fig 3 Comparison of Developments

Defensible Space Theory Part 3

Michael Kimmelman wrote at nytimes ‘penn-south-and-pruitt-igoe’

Pruitt-Igoe was the notorious St. Louis public-housing complex, demolished in 1972. Penn South is a cooperative in affluent, 21st-century Manhattan past which chic crowds hustle every day to and from nearby Chelsea’s art galleries, apparently oblivious to it. It thrives within a dense, diverse neighbourhood of the sort that makes New York special. Pruitt-Igoe, segregated de-facto, isolated and impoverished, collapsed along with the industrial city around it.

Fig1 Penn South NY Credit…Richard Perry/The New York Times

Fig1 Penn South NY Credit…Richard Perry/The New York Times

The thriving Penn South in Manhattan has much in common architecturally with Pruitt-Igoe, the outcomes being very different. They’re both classic examples of modern architecture,

Pruitt-Igoe was alienating, penitential breeding grounds for vandalism and violence. In Penn South, it worked. In St. Louis, where the architectural scheme was the same, what killed Pruitt-Igoe was not its bricks and mortar. (Minoru Yamasaki, who designed the World Trade Towers, was the architect.)

The two projects, aesthetic cousins, are reminders that no typology of design, no matter how passingly fashionable or reviled, guarantees success or failure.

Like Pruitt-Igoe, Penn South was a midcentury slum-clearance project. Designed by Herman Jessor as a modern cooperative for working class families, backed by the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, it called for 10 buildings spread across 20 acres between Eighth and Ninth Avenues, from 23rd Street to 29th Street. Two bedroom apartments cost $3,000 when the complex opened in 1962. (Those same apartments now sell for $100,000.) President John F. Kennedy stood atop a flag-decked dais in the bright May sun to dedicate it.

Steady income from maintenance payments and retail units in commercial buildings the co-op owned guaranteed Penn South a stable income. Tax relief from the city shielded it from escalating real estate values. Residents poured money into improvements. Repeatedly they declined the right to sell their apartments at market rates, preserving the ideal of moderate-income dwellings, adding facilities for toddlers and the elderly, playgrounds, a community garden and a ceramics studio.

It turns out that the very architectural traits that conventional wisdom said made tower-in-the-park projects like Pruitt-Igoe inhumane actually make these buildings ideal for retirees: the elevators and communal spaces, the enclosed green areas where it’s possible to walk safely, the openness and in-house programs.

Once again architecture evolves in bottom-up ways that architects and planners can never fully predict.

Defensible Space Theory Part 4

While form is important, e.g., the “lessons” learned by Oscar Newman in what he called “Defensible Spaces,” the real lesson is that the importance of form is not merely about the physical,

Fig 1,2,3,4 The Pruitt-Igoe Demolition Sequence. What Are The Lessons?

At shelterforce.org the article Public Housing: Building Communities vs. Providing a Place to Live By Richard Layman says successful housing isn’t merely a function of its form—design is not destiny—it’s also a function the economic and social mix present within the communities. what if the “demographics” of the tenants aren’t favourable to the development of strong public housing communities? Neal Peirce has a column, “A Nation of Public Housing,”about public housing in Singapore. Singapore, known for strong social control systems.

People can “move up” to larger units or different communities as their households and lives change. Singapore also subsidises social clubs of all types, and these programs are also present within public housing projects.The public housing program also confers to the tenant a kind of ownership interest in the apartment that can be sold, which helps build not only the “sense of ownership”

Lessons Learnt

- Commit to the creation of high quality housing that lasts as opposed to value-engineered construction that doesn’t last (the money might not be there for rebuilding when the time comes…);

- Inclusion of civic amenities (playgrounds, etc.) built into the project to build complete communities;

- Complementary social and community support and development programs;

- Provision of a variety of housing sizes and places to live;

- Elements of ownership: tenant has equity position/ownership interest in the property which can be sold/transferred, and contributes to the household wealth portfolio;

- Depending on the location of the project, integration of retail and other commercial spaces.

Defensible Space Theory Part 5

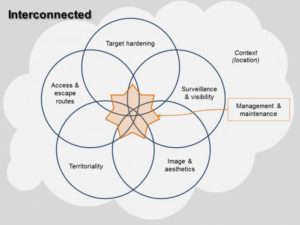

There are numerous references to CPTED online a couple of resources here wbdg.org and here wmaproperty.com are referred to below. CPTED evolved out of the USA. The UK has a similar version called by a different name – Secure By Design.

Safety in a neighbourhood has become a major concern by any potential home buyer, current residents and property developers alike as the value of a property can be affected by crime in the neighbourhood. A gated and guarded neighbourhood would be sufficient to reduce the crime but this is ‘yesterdays’ version of safety and security. Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) a multi-disciplinary approach to deter criminal behaviour through environmental design.

CPTED strategies are implemented by:

- Electronic methods: Electronic access and intrusion detection, electronic surveillance, electronic detection, and alarm and electronic monitoring and control

- Organisational methods: Manpower, police, security guards, and neighbourhood watch programs

- Architectural methods: Architectural design and layout, site planning and landscaping, signage, and circulation control. See below for further information.

Defensible Space; Oscar Newman coined the expression “defensible space” as a term for a range of mechanisms, real and symbolic barriers, strongly defined areas of influence and improved opportunities for surveillance that combine to bring the environment under the control of its residents.

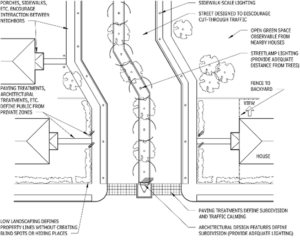

Natural Access Control; design streets, entrances, and neighbourhood gateways to mark public routes and by using structural elements to discourage access to private areas.

Natural Surveillance; natural surveillance maximises visibility of people, parking areas, and entrances. Examples are doors and windows that look onto streets and parking areas, pedestrian-friendly streets, front porches and adequate night-time lighting.

Territorial Reinforcement; define property lines and distinguish private spaces from public spaces, such as landscape plantings, pavement design, gateway treatments and fences.

Management And Maintenance; maintain neighbourhoods and residences and keep security components in good working order.

Legitimate Activity Support; a space or dwelling is encouraged through the use of natural surveillance and lighting and architectural design that clearly defines the purpose of the structure or space.

Defensible Space Theory Part 6

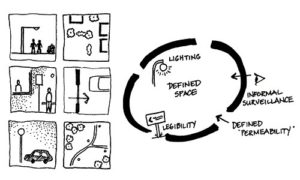

Fundamentally, security for the built environment is depicted in Fig 1 (see saferspaces.org.za ).

The terms used in Fig 1 have moved on and the latest terms are shown below with accompanying visual examples.

The UK’s interpretation of Defensive Space began with gov.uk saferplaces now archived and is now branded as Secure By Design the latest version is here ; securedbydesign – guides

Permeability or Access and Movement (Access and Escape Routes)

Defensive Perimeter

Passive Surveillance

Ownership (Territoriality)

Target Hardening

Management and maintenance